In Praise of Imperfection

Baseball will be less fun with Robo-Umps, and life will be less fun if we eliminate fallibility.

Next month, I will again be umpiring Minnesota amateur baseball in bucolic small-towns like Dundas, Miesville, and Faribault. Known colloquially as “town ball” it’s the rare spot in sports where a high school kid can play against a former pro, with college players and guys in their 20s and 30s filling out the roster.

At most parks, beers are $3, and local kids get a-buck-a-ball for shagging fouls and returning them to the concession stand.

I have the privilege of umpiring amateur baseball all summer, up and down the Cannon River Valley, in towns like Red Wing and Northfield, and out west of the Cities in Gaylord and Hamburg and Watertown and Green Isle.

And I have a confession to make, as long as you promise not to tell any of the players or managers: sometimes I miss a call.

You know the old saw, “A tie goes to the runner”? Well, it’s not true. There are no ties in baseball, and on a bang-bang play at first — what umps refer to as a “whacker” — I have to make a call, safe or out. Usually I get it right.

When I’m behind the plate, I’ll see around 250 pitches in the course of a nine-inning game, and any pitch that is not struck at by the batter, I need to call a ball or a strike. As the legendary umpire Bill Klem said, “It ain’t nothin’ till I call it.” Most of the time, I call it correctly.

Occasionally, a manager will take umbrage at one of my decisions, and he will jog out onto the field to have a civil conversation with me about the merits of accurate officiating, and possibly he will comment on the state of my vision or the eternal destiny of my soul. From the dugouts, players chirp about my strike zone, sometimes with encouragements like, “You’re better than that!”

When players and managers and fans comment on the errors in my judgment, I often sneak a look at the scoreboard, and most of the time the very team that’s unhappy with me has logged a few errors themselves.

The baseball box score was invented in 1858, and by the end of the 19th century, the number of errors committed by each team was listed in the box score and printed in newspapers around the country. Baseball is the one sport in America where mistakes are included in the official report of the game, for all to see.

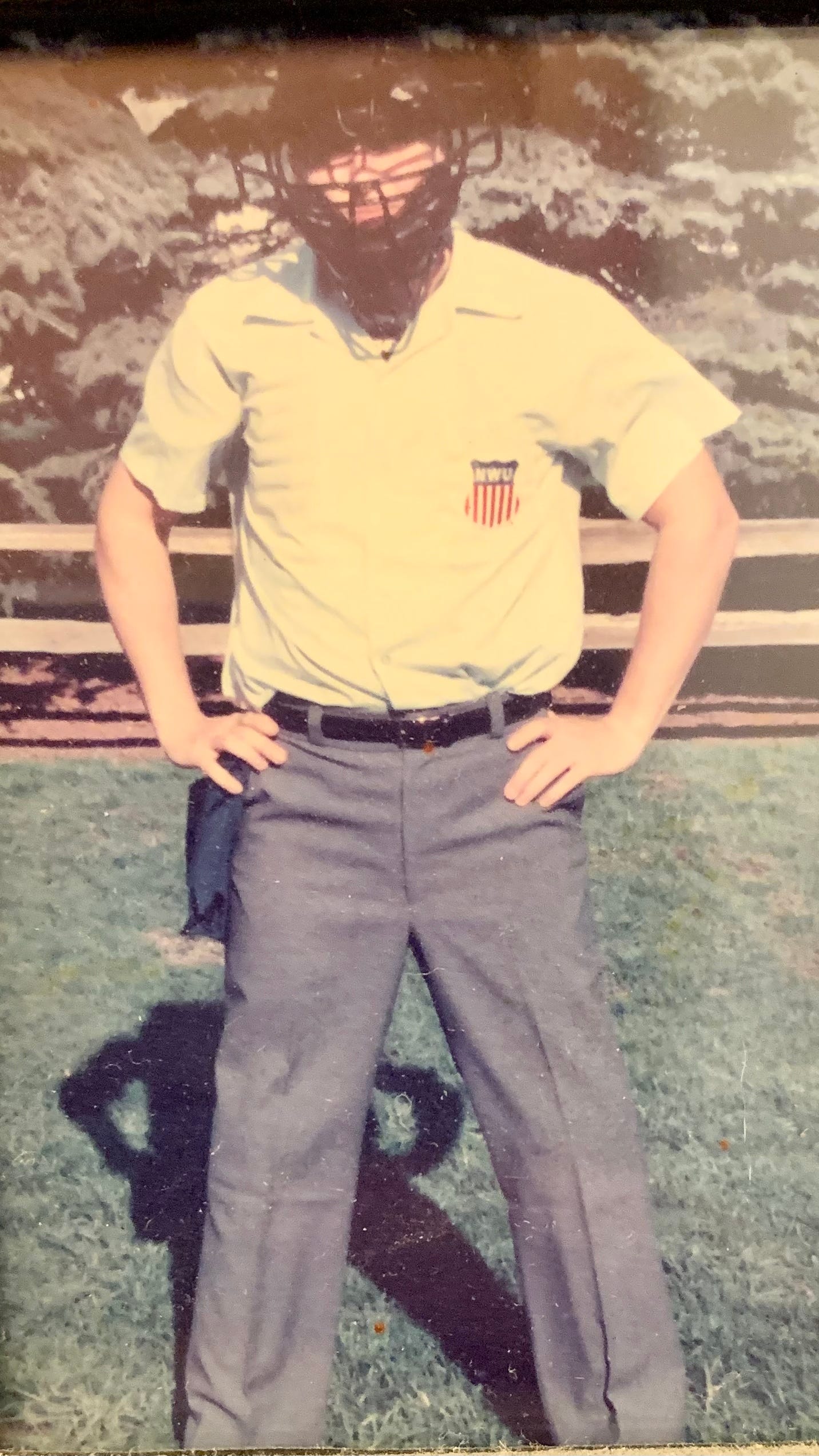

I started umpiring when I was 14, and even before that I took up the odd hobby of collecting rule books. I’d write letters to the U.S. Volleyball Association and USA Table Tennis, with a self-addressed, stamped envelope, requesting their official rules of play. They’d arrive, and I’d study them, then put them on the shelf with their compatriots. Obviously, studying the “rule book” of Christianity — the Bible — as a profession wasn’t much of a leap.

I umped baseball for many years. When Lily was born in 2001, I retired, after working my one and only NCAA Division I game. In the summer of 2021, bored out of my mind during Covid, I unretired. I’ll ump a few dozen games this summer, mostly alone, sometimes with a partner.

One of the things that I like most about officiating is that I’m becoming better at it. It’s not an endeavor that’s perfect-able — just last year, Pat Hoberg umpired the first perfect game behind the plate since the MLB has been using computers to grade umpires, and it was in the World Series no less. But that game is the exception that proves the rule — in his most recent game behind the plate last week, Hoberg missed six pitches (still pretty damn good).

After every game in which I have a partner, we sit on camp chairs in the parking lot drinking a beer, and talking about the game — what we did well, what we could do better. There’s no passive aggression: my partner will tell me about the calls he thinks I missed, and vice versa. We talk about other games we’ve had during the season with unusual scenarios or coaches who are notoriously argumentative.

It’s rare in my life, to have something that I’m getting better at, even though I’ve done it on and off for 40 years, to have an endeavor that I ask other guys who are virtually strangers to tell me how to do it better, to do something that’s open to immediate public scrutiny.

But mostly, to do something that includes all those aspects and is, by its very nature, not perfectable. Umps getting calls wrong is part of the game, a variable that over the long season balances out its effects over all teams. It’s as much a part of the game as the fans yelling at the umps for missing those calls.

We’ve mitigated a lot of human fallibility out of life. Apps use algorithms to tell us who we should date, and lane assist beeps at us when we wander over a yellow line. These are, I suppose, natural evolutionary advances, meant to ensure our propagation and protection. Nevertheless, I’ve come to realize that the human endeavors I enjoy the most at this point in my life — hunting, fishing, umpiring, writing, parenting — not only cannot be perfected, they remind my of my fallibility regularly. I fail at them as much as I succeed.

MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred says that by next summer, robot umpires in some form will be part of Major League Baseball, calling balls and strikes. That’s a tragedy. There’s something special and beautiful that baseball, like life, is replete with mistakes and imperfections. Trying to engineer human fallibility out of the game will not make it more attractive to young generations. It will just make it a less human game.

I’m just thankful that robo-umps won’t be coming to the small towns where I ump, at least not in my lifetime.

Sitting in the lunchroom, laughing aloud at “… the merits of accurate officiating, and possibly he will comment on the state of my vision or the eternal destiny of my soul.”