I didn’t fly on an airplane until I was 15. When I was young, my family took long road trips. My parents owned a Ford LTD station wagon — a “Country Squire” model, replete with faux wood paneling. My dad wasn’t a doofus like Clark Griswold, but otherwise our trips did somewhat resemble National Lampoon’s Vacation.

My dad did most of the driving, and my mom read books aloud to my brothers and me — the Little House on the Prairie and Chronicle of Narnia series were the family favorites.

But sometimes my mom would drive so that my dad could take a nap. I vividly remember one of those times when she was driving. We were somewhere out West — in Montana or Wyoming — on our way to a national park. The following scene must have happened in the course of less than two seconds:

Something fell off the back of a truck that was ahead of us — a box of some sort — and bounced straight toward us.

My mom shouted, “Douglas!”

My dad, in the passenger seat, woke up, looked out the windshield, and calmly said, “Drive over it.”

She did as he said, and the station wagon blew right over the object.

The box must have been empty, but my dad had no way of knowing that. He just made an instantaneous judgment that driving over it at 80 miles per hour was less risky that trying to dodge it and ending up in the ditch, or worse.

(Clark Griswold, famously, fell asleep at the wheel and wasn’t so lucky.)

I don’t know if that’s a perfect metaphor for having a speaking gig canceled, which happened to me this week, but it’s a similar feeling: something dangerous is unexpectedly thrown into my path, and I’ve got to decide how to keep moving through it without getting derailed.

In January 2015, our family’s custody case was re-opened — one of my children prompted this, and I supported him.

The person who opposed my attempt to gain custody of my three children used the internet to air grievances and corral support. To a lesser extent, that had happened during the 2009 divorce as well, but in 2015 it was stickier; the internet had evolved in such a way that it amplified conflicts like ours, and with platforms like Twitter and Facebook, everyone had a voice.

Truth was immaterial. The messiness of my life was mine and mine alone. Friends — most of them public figures as well — understandably didn’t want my problems to spill onto them. “You’re radioactive,” one said to me.

Two prominent Christian women publicly cut ties with me. That was the first domino to fall. Others followed. A friend with whom I’d worked for years and with whom I’d traveled to the French spiritual community of Taizé called to tell me that his lawyer advised him to stop talking to me. (I remember where I was when he called to tell me that: in the narthex of Solomon’s Porch.) Lawyers at Fuller Seminary, my alma mater, told the dean of the D.Min. program, where I’d been teaching, the same thing. I stayed home from the Christianity21 conference in Phoenix that I’d co-organized; I sent a video message, explaining that my absence was to support my child who’d come to live with me full-time. The video was not shown, and as a result, people had only what they were reading on the internet to inform their opinion about me.

I had a book come out in February, 2015. It flopped, the victim of an online campaign to cancel me. One endorser tried to pull his endorsement off of the back cover. The pastor of Mars Hill Church in Grand Rapids, Michigan, called me in tears and rescinded my invitation to preach on Palm Sunday.

In The God of Wild Places, I describe that period thusly:

Trauma hit me in two surges: the divorce itself, then the aftermath. The first, like a bigger-than-expected wave caught me standing knee-deep in surf and knocked me sideways; then, as I was regaining my balance, the second wave hit, threw me to the seafloor, washing-machined me senseless.

I had a recurring dream during those years, that I was screaming for rescue at the top of my lungs, but no sound came from my mouth. The harder I screamed, the more panic I felt, but still no sound. No one could hear me.

Panic is one word that describes my experience for the better part of a decade. Anguish is another. So is terror. Those three unwanted guests invaded every aspect of my life, waking me in the middle of the night and stalking me during the day. The earth didn’t spin a revolution without one or more of them afflicting me. They were my predators.

I asked Courtney what she remembers about 2015, and she wrote this:

My physical heart hurt within my chest. When I sobbed, I would press my my hand over my chest in a futile attempt to hold my own heart. It’s the only time in my life that I have lost all hope and optimism. I could not believe that people were buying the lies.

The thought that my problems did this to her, as you can imagine, is hard to read.

On November 23, 2015, as I stood in the atrium of the Marriott Marquis hotel in downtown Atlanta, my phone rang. I was attending the American Academy of Religion’s annual meeting in my role as an acquisitions editor for Fortress Press. I saw on the caller ID that is was my attorney, and I stepped into the space between sets of revolving doors — again, I remember exactly where I was — and answered.

“You’ve been awarded sole custody of the children,” she said. “Starting next Monday.”

The call was brief. She said we’d talk later in the week, once she’d worked out details. She congratulated me, said that the Court had finally come to the right conclusion. I thanked her and hung up. I walked outside, where valets were running to fetch cars, and religion professors wearing name badges and pleated khakis strolled past me. My world had changed. And I couldn’t believe that I’d survived it.

It had been a long eleven months. We’d endured many court hearings, met with guardians ad litem, therapists, and school counselors. I’d undergone yet another psychological evaluation (and had my car stolen during one session — insult, meet injury). I’d collected reams of evidence, and ultimately submitted to the court 1,043 pages of exhibits. And now, I’d been awarded sole custody.

I knew it wasn’t over. To use a sports analogy, the game had been won, but we still had a couple minutes on the clock. Sure enough, the drama of the next few weeks was intense. But it didn’t change the outcome.

The kids came to live full-time with Courtney and me, and the last ten years have been unmitigated joy — watching them grow. Innumerable hockey games and debate tournaments; weekends at the cabin; college visits; canoe trips. They’re thriving now — we were all together last weekend in Texas, along with my mom. Sitting at a dinner and listening to the three of them banter may be the most delightful sound I can imagine.

What I didn’t know in 2015 was that a decade later, as I’m cruising along the interstate of life, hazardous objects still fall into my path.

Case in point:

Knowing that I had a new book coming out in 2024, my friend, Tripp Fuller, invited me to be a keynote speaker at Theology Beer Camp 2023, his annual conference — my first significant speaking invitation in several years. Tripp has been a stalwart friend for nearly two decades, and he didn’t flinch when online trolls came after him for inviting me. Finding no purchase with Tripp, the trolls attacked the other speakers at the conference, hoping that they would pressure Tripp to cancel me. (One prominent podcaster called to ask me questions about the divorce; I put him on speaker phone with one of my kids; I meant it to be awkward for him, and it was.) When the other speakers didn’t cave to the pressure, the trolls aimed their fire on the church that was hosting the conference.

I can’t blame the church for flinching. They didn’t know me, and it’s disconcerting to think that you might have a terrible person stepping onto your stage. Tripp asked if I’d have a Zoom meeting with the church staff to allay their concerns and answer their questions. Tripp also assured me that he’d move the conference to another venue before he’d cancel me — in his words, “If you and I are the only people at Beer Camp, you’ll still be a speaker.”

Before the Zoom, anxiety plagued me. I couldn’t sleep, and I paced around the house — all the old feelings were coming back. Courtney sat me down and smudged me with sage. She told me to turn on my camera a couple minutes late so that the people on the other end would have to look at my profile pic, hoping that seeing me with my wife and kids would humanize me.

When I finally turned on the camera and the meeting started, something unexpected happened. One of the pastors leaned into the camera and said,

“Tony, before you say anything — I have spent the last two days reading court documents on the Hennepin County website. I see the truth of your situation. You have nothing to apologize for or explain. We’re sorry that we’ve put you through this, and we look forward to welcoming you to our church.”

I was stunned. That had never happened before. Someone actually took the time to seek the truth rather than believe internet bullies who were fomenting lies and hate.

It happened again this week. I was supposed to fly directly from seeing my kids in Texas to speak at a church conference, a rare high-profile gig for me. Unlike the pastor above, the people in charge of this conference did not do the work, did not seek the truth. Instead, they canceled my appearance.

(Side note: These are educated, liberal clergypersons with masters degrees and doctorates. They call out lies on the internet when they come from conservatives, but their confirmation bias blinds them to lies when they come from their own tribe. Long ago, I tried to fight the online lies, but it didn’t work. In fact, it made it worse. (See Brandolini’s Law.) So I’m not going to re-litigate the situation, because it wouldn’t work anyway. I’ll just say this: It could happen to you, too, if someone were to have a vendetta against you and used the internet against you, it would probably work. At the very least, it would cause you a great deal of grief.

And if you’re a casual observer of a situation like mine, be skeptical. Be very skeptical.)

When this stuff bubble up again, the responses from those close to me vary:

My kids and most of my friends roll their eyes and say, “This is still happening?”

Courtney gets angry, not only because she can’t believe that people are so easily taken in by lies on the internet, but also because the implication is that she would marry an abusive person. (Which is laughable. Anyone who’s ever crossed paths with Courtney, much less taken a yoga class or an Enneagram class with her — hell, anyone who’s had their photo taken by her — knows that she is goodness and light and love. She is a self-preservation Enneagram 7. She avoids conflict and conflictual people. She is a feminist of the first order. To believe that she could marry someone who is angry, abusive, and narcissistic is, frankly, absurd.)

And me? I got reacquainted with my old enemies: panic, anguish, and terror

I present as strong, maybe impenetrable. I get it. I’m an Enneagram 8, an ESTJ. But getting canceled sends me into a tailspin.

My career is over, I think.

Why do I even keep trying? I wonder.

I become despondent. Everything is a threat. Everyone believes the lies. That’s the narrative in my head.

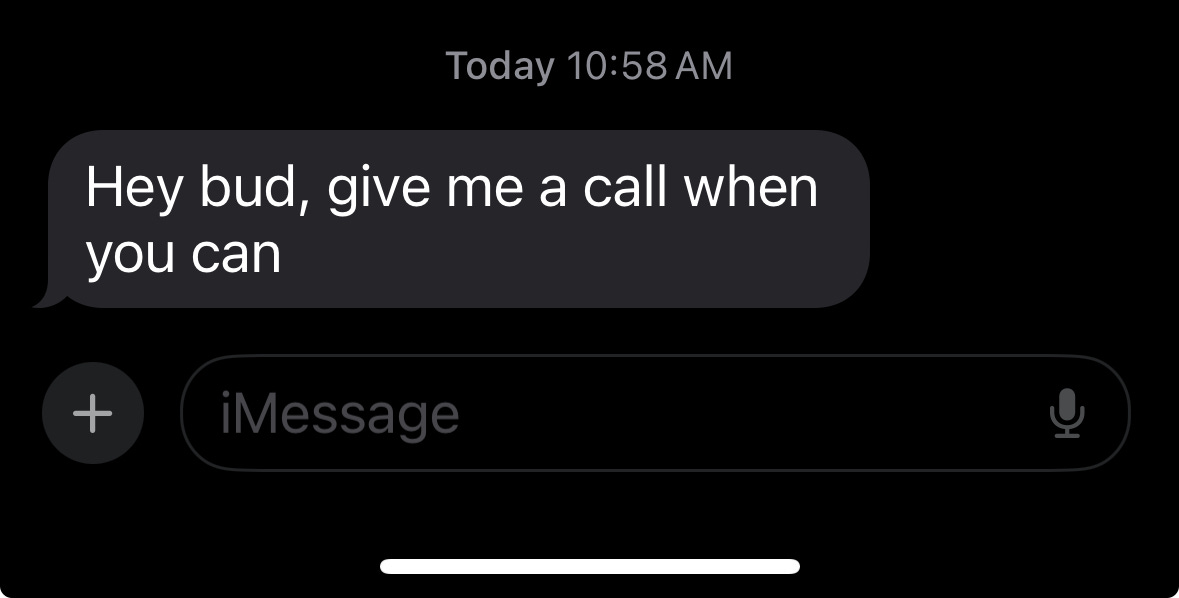

For example, on the same day that I was informed of the cancellation, I was elected to the board of a conservation organization. The next day, I got this text from a friend who’s also on that board:

I panicked. I knew it was bad news — someone on the board or at the national headquarters had googled me. They were reconsidering the election. They wanted me to gracefully step aside.

I waited a day to call him back, preparing for the worst.

Then I called him.

He wanted to talk to me about ice fishing.

It had nothing to do with my troubles on the internet.

But the anxiety took a toll.

I can write litanies of caveats:

Others have it worse than me.

Way worse.

In spite of my troubles, I’m a privileged person.

I’m not without sin.

So I’m not writing this essay to defend myself, nor am I falling on my sword. I’m writing because Courtney said, “You should write about this. People should know what this does to you and to us.”

It took me a couple weeks — and a fantastic trip to Virginia to speak at two churches — for me to get over the cancellation.

And it took Courtney saying, “You had a speaking gig canceled. You haven’t been canceled.”

Of course, she’s right. As usual.

My life is so different than it was in 2015.

I’m so different.

In the second century AD, the Stoic philosopher (and former slave) Epictetus wrote,

“When I see an anxious person, I ask myself, what do they want? For is a person wasn’t wanting something outside of their own control, why would they be stricken with anxiety?”

When that anxious person is the person in the mirror, it’s a lot more challenging to remember that the anxiety is about something that’s out of my control. It takes some time and the love of family and friends to re-center me.

My life is great. I’m surrounded by love.

I’ve just got to remember that when a box falls off a truck and bounces toward me: just drive over it. Everything will be fine.

Thanks for reading. If you like this post, I write a lot about this era of my life in The God of Wild Places. And you can also subscribe — either free or paid — for more posts.

Tony - you’re a great story teller. I wish these truths weren’t your reality, but they are. I’m glad you’re surrounded by the love of family and friends today. And, I’m proud to be someone on that friend list.

Spending time with you at Beer Camp in 2022 is one of my favorite memories! Love you, Tony!